China’s Social Credit System in 2021: From fragmentation towards integration

Updated on May 9, 2022

Key Findings

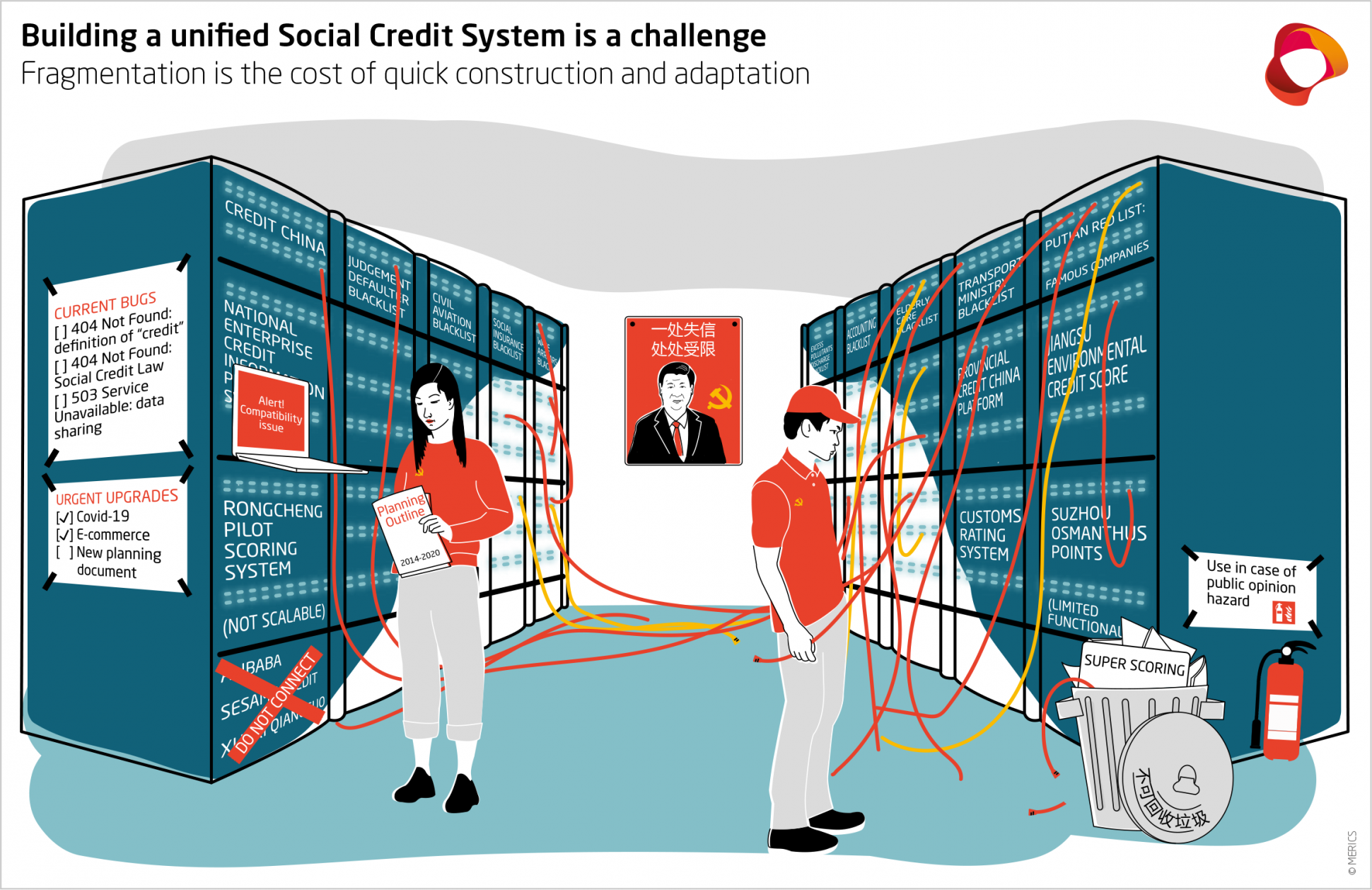

- The Social Credit System is part of Xi Jinping's vision for data-driven governance. Government organs across regions and administrative levels should join hands to create a coherent information ecosystem. Data-sharing challenges continue to hamper this effort.

- There will not be a unified “Social Credit Score” that rates individual behaviour. An all-encompassing scoring system was not part of the original plan. Instead, efforts have been focused on the establishment of comprehensive digital files that track and document legal compliance. Pilot projects that used points-based systems to steer behaviour beyond what is legally required have been discontinued or limited to voluntary participation.

- The Social Credit System is a highly flexible tool that can quickly be applied to address new policy priorities. During the Covid-19 pandemic, government agencies rapidly issued a slew of directives to implement pandemic-related regulations.

- The flexibility of the system also comes at a cost: fragmentation. The Social Credit System is regulated by thousands of documents, but there is no clear definition of “credit” and substantial regional differences exist in implementation and evaluation standards.

- The uneven implementation presents risks for individuals and companies alike. They have to navigate various regulations, lists and rating systems. There is an acute risk of “credit” becoming an arbitrary term that can be applied with disproportionate punishments.

- The Chinese government is aware of these issues and has initiated steps to more clearly define “social credit”, establish practises and improve measures for credit repair. Work on a Social Credit Law has started, but it may take years until core mechanisms become standardised nationwide.

- The private tech sector continues to be excluded from the development of the official Social Credit System. But payment and consumer platforms like Alibaba’s Sesame Credit have created their own trust-rating initiatives.

- The Social Credit System remains the least digitised of China’s tech-driven monitoring and surveillance initiatives. It relies heavily on human investigations, reports, and decisions. This also leaves room for traditional vectors of individual and political influence.

- The party state will further build up, streamline and integrate digital monitoring and surveillance activities. More invasive domestic security platforms and initiatives have advanced rapidly and with significantly fewer limitations than the Social Credit System.

1. Introduction: The Social Credit System enters a new stage

The year 2020 marked the end of a key construction phase of China’s Social Credit System (SoCS) – one of the cornerstones of the Chinese party state’s quest for data-supported, efficient rule. The general framework and key mechanisms have been established. Numerous reports and planning documents have been drawn up to guide the SoCS into the next phase, which aligns with the upcoming 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).1

There is still dynamic development and debate about how it should be adjusted. It is crucial to understand how this quickly evolving system works and anticipate how it will develop in the coming years, as it will become a defining feature of Chinese governance over the next decades. It also directly affects foreign actors with a presence in China.

The SoCS itself is not tasked with conducting political surveillance of individual behaviour. Its role is more clearly limited in recent party and policy documents. Instead, these functions and political needs are addressed by other domestic security systems. In addition, a variety of commercial scoring systems have popped up across China, which operate independently of the SoCS.

The SoCS is often envisioned as a fully digitised and data-driven system. And indeed, digitalisation and informatisation are key items on China’s political agenda, with the explicit goal to “use big data to modernise national governance”, a theme set to feature prominently in the coming Five-Year Plan.2

But despite these lofty proclamations, 2020 also laid bare how lacking digitalisation still is in certain areas. In practice, it serves as an umbrella term that can mean anything from simple operations such as digitising forms and uploading spreadsheets, to the use of big data analysis to generate insights for policymaking and law enforcement.

Nonetheless, the party state’s ambitions remain clear: To expand, integrate and analyse existing data sources to improve and consolidate CCP rule. Despite current fragmentation, this also spells the way forward for the continued evolution of the SoCS.

2. The Social Credit System is legally ambigious

International media coverage has often focused on 2020, the end date of the major policy blueprint issued by the State Council in 2014, creating the impression that the SoCS would spring into action as one integrated system by that year. But, despite the fact that some of its key mechanisms have been in place for years, the SoCS today is not a unified, standardised system. What is established today can best be described as a policy framework that encompasses a large number of initiatives, or as a “system of systems.”

2.1. A brief history: From financial credit to socio-political panacea

The roots of the Social Credit System (SoCS) go back to the early 1990s as part of attempts to develop personal banking and financial credit rating systems, especially to facilitate lending in rural areas, where individuals and small enterprises often lacked documented financial histories. The first blueprints of the SoCS were drafted in 2007 by a group of government bodies.3 Since 2011, there has been a marked shift in the SoCS’s objectives from financial credit rating system to panacea for a broad set of socio-political ills.

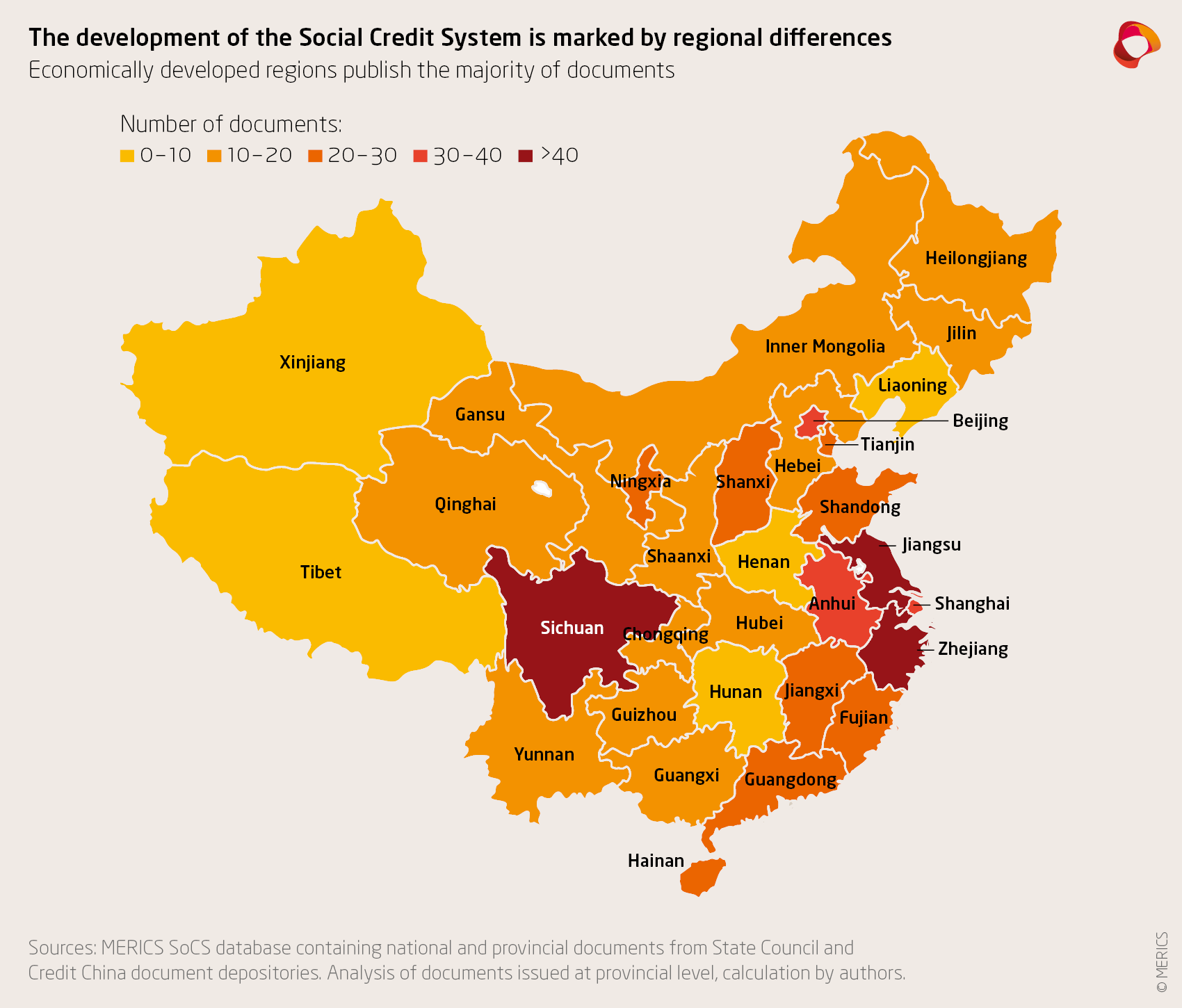

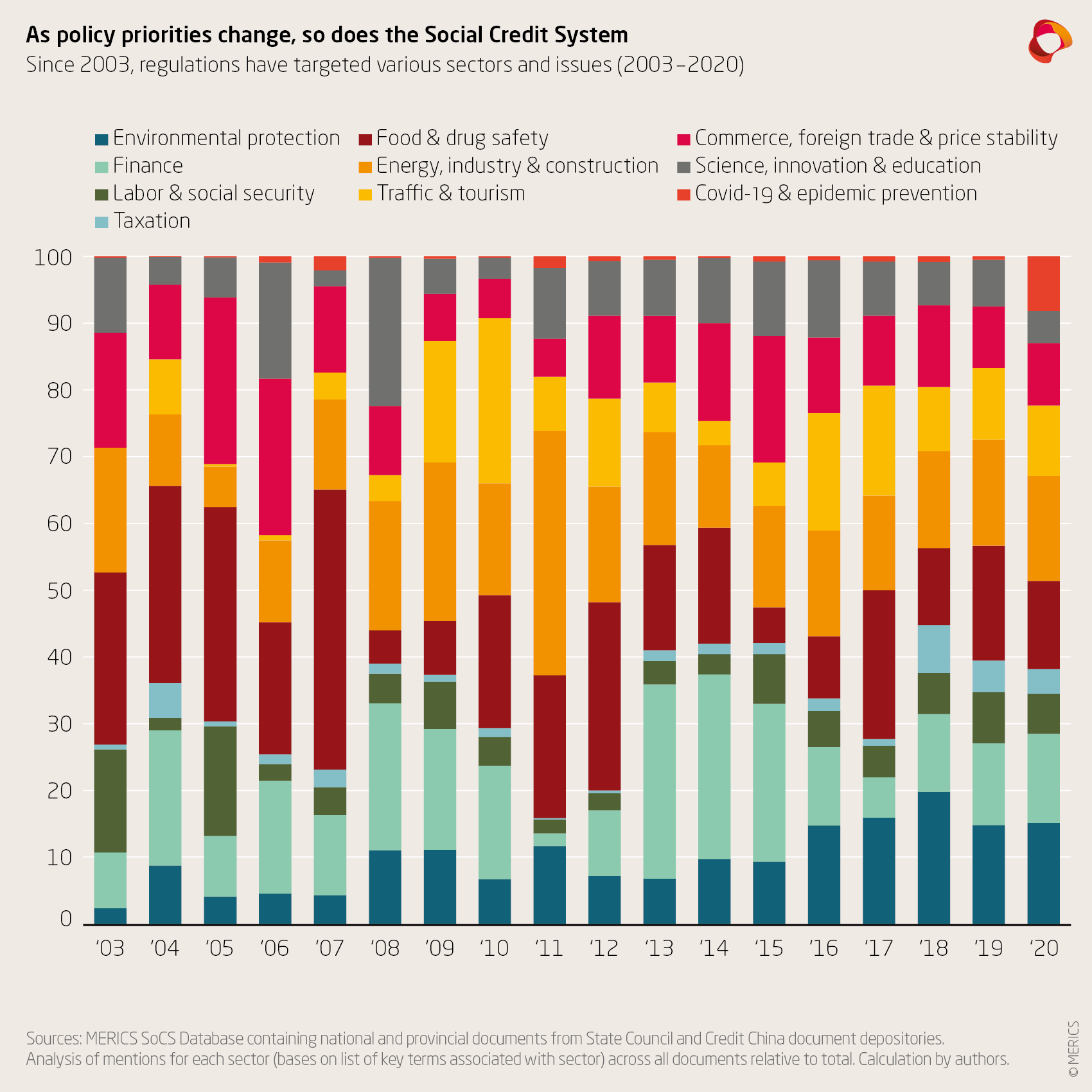

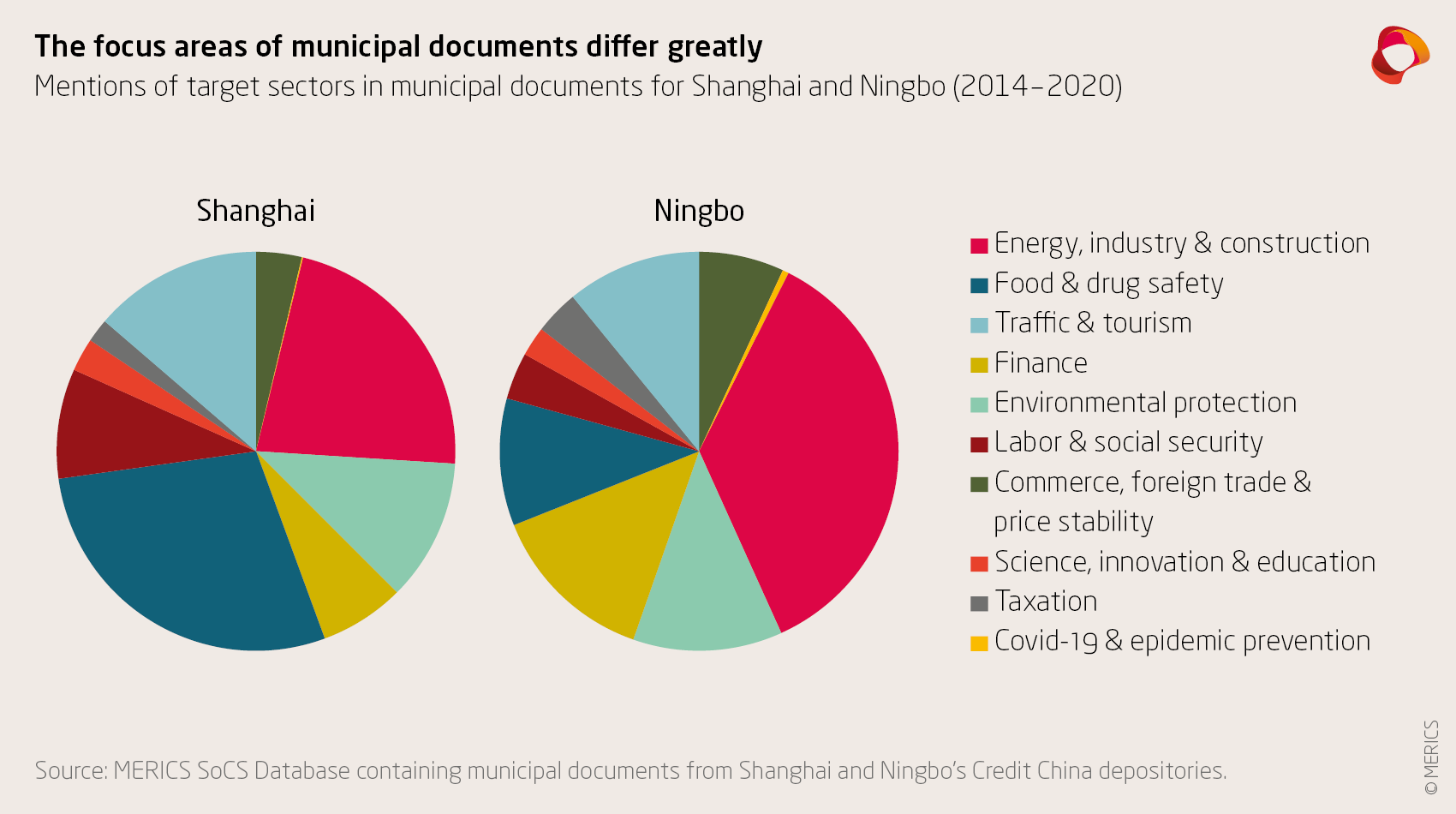

Complaints that China is a “low trust” society have long been widespread: Chinese society is seen as suffering from a moral vacuum as a result of the turbulent economic and social changes since the beginning of reform and opening in 1978. The growing wealth in economically developed regions came at a price, as they suffered most from insufficient supervision of market actors, environmental and food safety scandals, violations of labour law and IP rights as well as widespread corruption and rent-seeking (see exhibit 1 on SoCS regional foci).

Since 2014, State- and Party Leader Xi Jinping declared “comprehensive law-based governance” a top political priority. Ensuring that all individuals, market actors and government organs play by the rules is seen as a prerequisite for stable economic growth – and hence for social, political and regime stability.4

Within this broader political context, the Social Credit System’s main purpose has turned to enforcement of existing laws and regulations. This significant expansion culminated in the “Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014-2020)”, issued by the Chinese State Council, and led to its most crucial period of construction.

Social credit has become a fixture of the new ideological canon of “Xi Jinping Thought on Rule of Law”.5 In January 2021, the CCP’s Central Committee issued a new roadmap for the “construction of a rule of law society” until 2025. It includes a section on the SoCS, highlighting its importance for China’s legal development agenda as a supporting pillar of the legal system.

2.2. Finding the Social Credit System in a regulatory jungle

The broad range of policy goals projected on the system explains why what is generally translated as “social credit” is not a clearly and legally defined concept. Documents and discussions of the system contain a set of terms that range from financial creditworthiness (征信) to broader trustworthiness, law-abiding behaviour, or even moral values such as honesty and integrity (诚信/守信).7

The vagueness of “social credit” has enabled China’s local authorities to use the catchphrase to enforce (often unrelated) policy priorities through highly localised initiatives.

Today, 47 institutions (with partly conflicting intentions) are involved in shaping the system. These include the State Council as cross-ministerial coordinator, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the People’s Bank of China in the lead. Many of these institutions are also responsible for implementing the system by establishing and managing platforms to track “social credit” in their respective policy fields.

Examples include financial regulators, or supervisory bodies tracking legal compliance in such areas as environmental protection, food safety or, most recently, epidemic prevention. Regional and local authorities are also closely involved. However, despite the busy rulemaking for the SoCS, there is no central, structured depository of related documents. Thousands of documents can be found on ministry websites, and those run by provincial and municipal governments.8

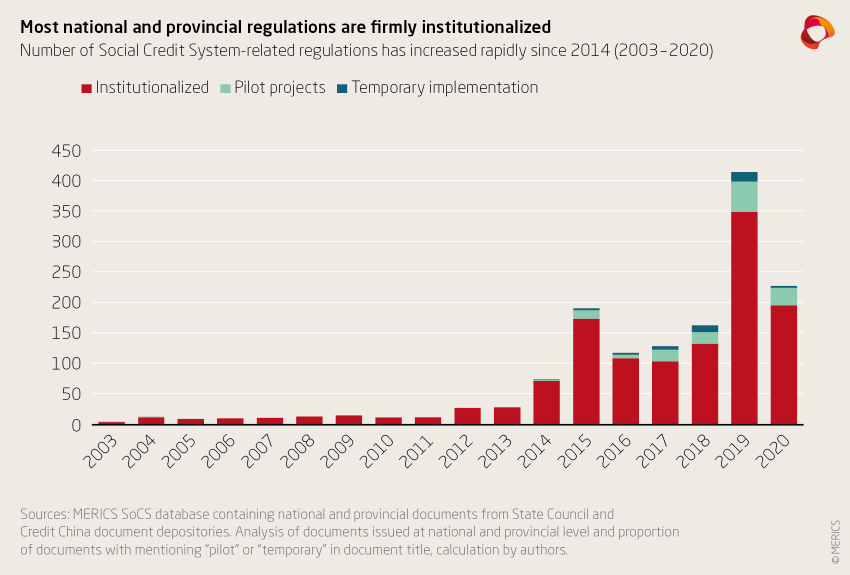

Documents published by the main regulatory agencies since 2003 show that the number of published regulations has risen steeply since 2012. Output peaked in 2019 – the year that a new initiative on data-driven governance was introduced.

There are also a growing number of laws and regulations that refer to SoCS as an enforcement mechanism. These include national level laws such as the Foreign Investment Law (2019), the Vaccine Administration Law (2019) and the recently adopted Biosecurity Law (2020). The low number of temporary “trial” or “pilot” documents also speaks to the fact the system is well-established (see exhibit 2).

Despite the open accessibility of these regulations, the SoCS remains opaque due to the sheer volume and decentralised storage of information. The regulatory jungle aptly illustrates the messy and inconsistent nature of the system as a whole.

While the central government encourages a certain degree of experimentation, it is increasingly concerned that SoCS has become so opaque that the system can no longer deal with the central policy challenges it originally sought to address. It has set unifying terms, standards, and practices as the priority for the next phase. Work has also begun on a comprehensive Social Credit Law. A first draft was formulated for internal review in December 2020.11

3. The Social Credit System has become a flexible tool for speedy and strict enforcement

The SoCS has arrived at the end of its crucial six-year construction phase. This represents a good time to take stock of its evolution. One key finding: the system is in many ways less coherent than top-level government blueprints demand. This inherent flexibility allows it to be swiftly redirected towards rules enforcement in changing policy circumstances, something amply displayed in China’s pandemic response.

3.1. Ensuring that all societal actors play by the rules

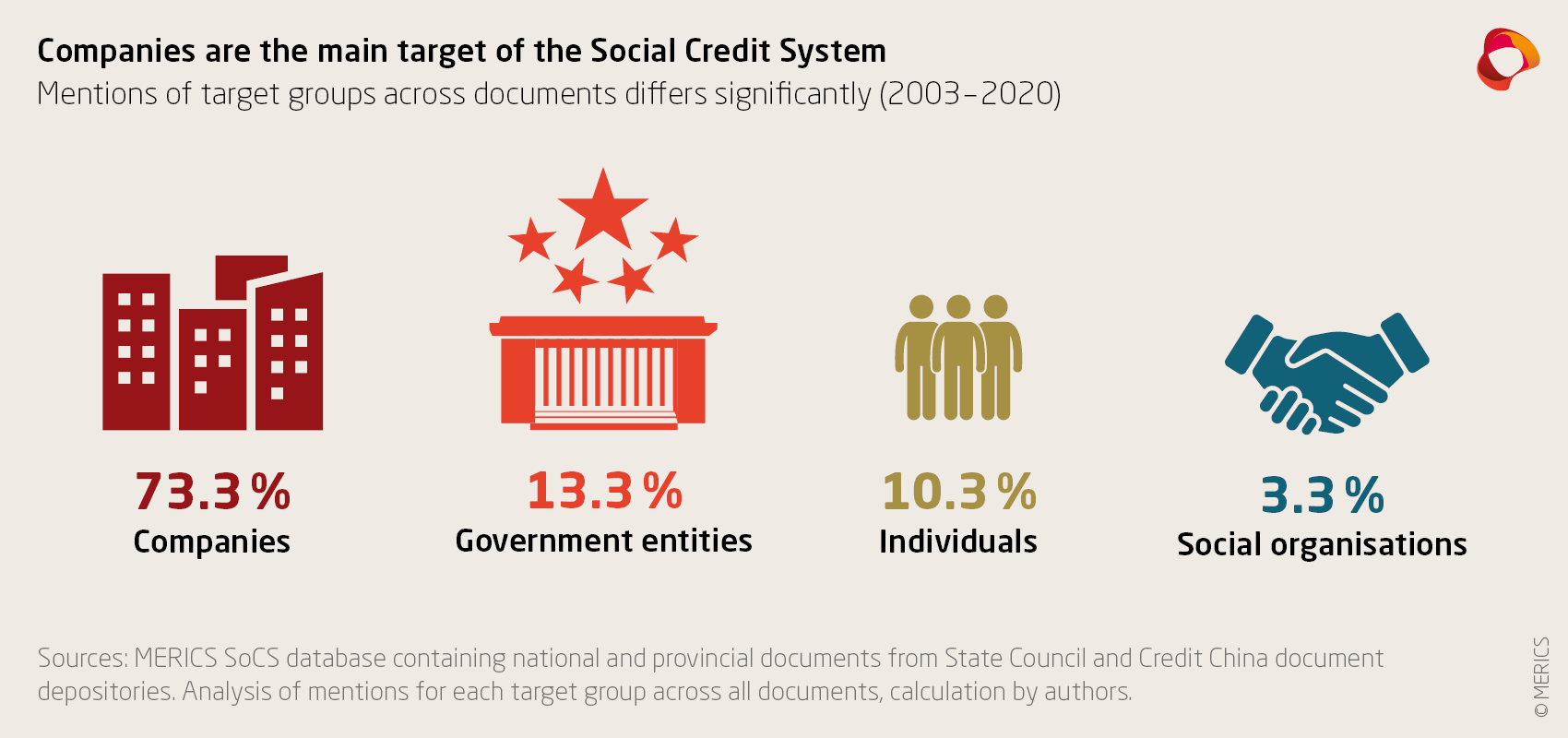

From the start, the SoCS had a wide remit to target individuals, enterprises, social organisations, and government organisations (see exhibit 3). Only CCP organisations are exempt. However, the main target group has been companies, in line with the overall policy goal of increasing public trust in commercial products and services and in China’s market economy.

Ensuring companies comply with law and regulation is achieved through both centralised tracking of violations (recorded in the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System) and a patchwork of sector- and region-specific rating systems.

Foreign enterprises with a registered presence in China (legal persons) are included in the SoCS system on equal terms with their Chinese counterparts. Social organisations (i.e. any non-governmental entities) remain a small group in numerical terms, but their inclusion is important to note as it also affects foreign NGOs with representative offices in China.

In dealing with individuals the SoCS is largely focused on debt repayment. Despite this, major violations of laws are also tracked and sanctioned. Foreign individuals with residence in China have occasionally been affected, especially in their function as legal representatives of a company or for debt default.12 Government agencies are also a target group, especially in cases of local government debt and contract defaults, but overall efforts have focused on assessing their performance and incentivising them, rather than sanctions. Ultimately, the different target groups of the SoCS should be considered as “pillars” of one, albeit fragmented system.

The SoCS does not establish any new substantial obligations on corporate or individual behaviour. It remains limited to tracking compliance with, and enforcement of, laws and regulations.13 It does, however, notably increase reporting duties towards supervisory agencies to channel data points into the system.

It is important to note that the SoCS remains an extension of the existing legal and administrative system under party-state control. The official limitation to “enforcement of laws” does not prevent overreach and human rights violations:

- First, the SoCS enforces all laws and regulations. This includes repressive ones such as censorship regulations, or those that lead to discriminatory treatment of companies. It also enforces the growing list of regulations aimed at tackling anti-social conduct, standardising and restricting civic behaviour in line with “socialist core values”, as proclaimed by the leadership.

- Second, government organs can abuse the system to punish individuals for unrelated behaviour. In Inner Mongolia, parents withdrawing their children from schools with mandatory Mandarin education curriculum were threatened with blacklistings.14

- Third, government organs or public institutions can be overeager to use the official “credit” assessment beyond its defined purposes, such as when some public schools decided to exclude students from placement whose parents were on the debt-defaulter list.15

3.2. Tracking compliance allows servere and targeted sanctions

In the past, major debtors and serious offenders involved in scams, or violators of food safety or environmental standards, were able to move on and repeat misdeeds without significant consequences elsewhere. To fulfil the SoCS’s primary objective of tracking and enforcing overall compliance, two things are required. First, the government must be able to identify all actors consistently over time and in various locations and, second, the information needs to be shared.

Unified identification number and integration of information and ratings

Official discussions of SoCS have stressed the need to overcome data islands. Regulations and a number of Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) between government departments attempt to tackle their notorious reluctance to share information and resources. They are now required to actively collaborate and to integrate their data across institutions and regions.

A key part of SoCS building in recent years was making sure that all individuals, private entities or organisations nationwide could be identified by a standardised identification number. Identifying and attaching credit files to individuals through their unique personal identity number was relatively straightforward. Companies, social organisations and other institutions were assigned individual numbers based on a unified system. This has largely been accomplished, including for foreign companies and NGOs.

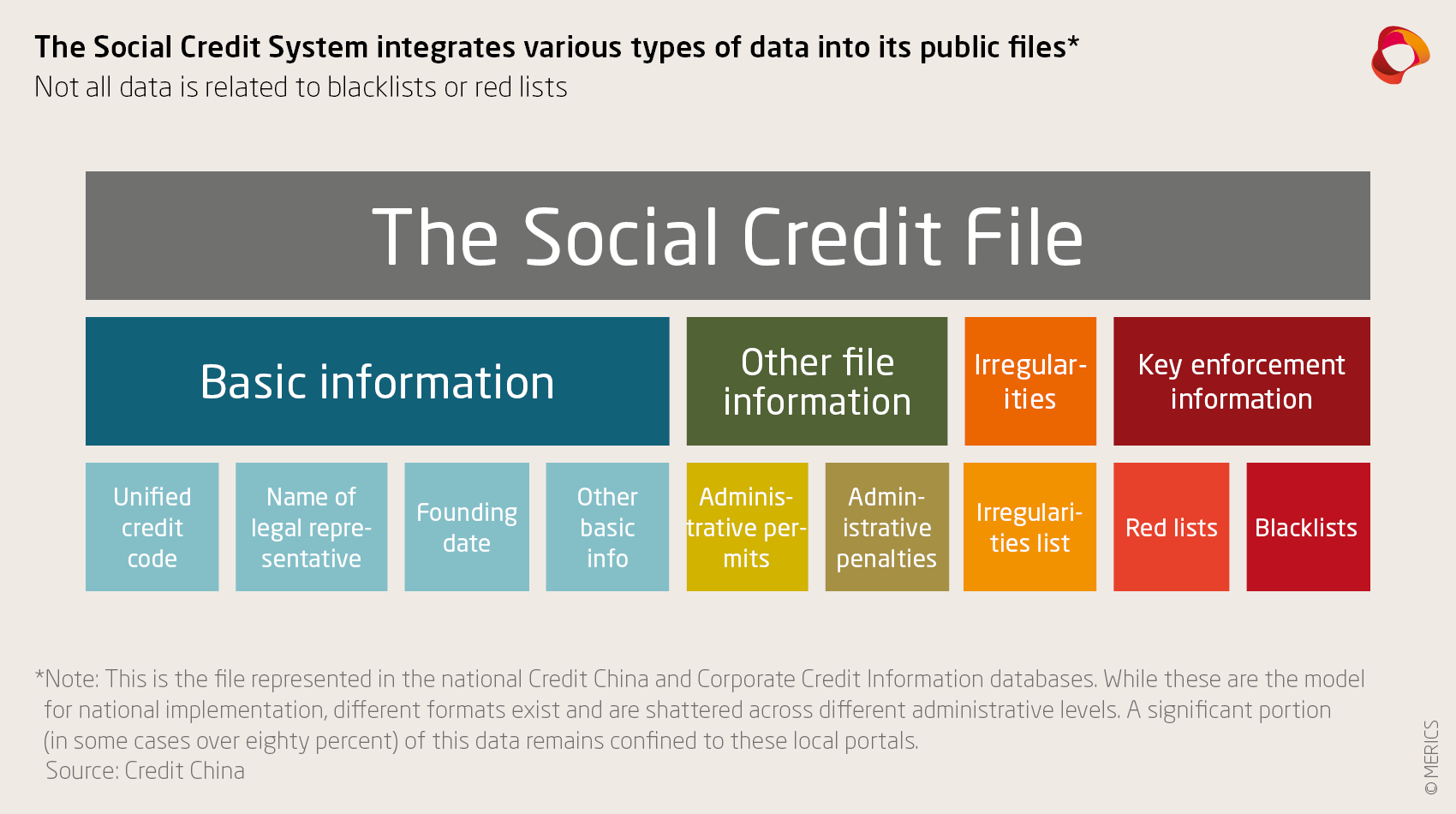

For companies, the data that the SoCS integrates broadly falls into four categories: basic information, information on administrative penalties and permits, any irregularities, and red list or blacklist information (if applicable). There is no unified credit score, rather national and local platforms use different evaluation or rating systems. Nonetheless, these aggregated digital files of compliancerelated information contribute to law enforcement (exhibit 4).

Blacklists, red lists and public naming and shaming

Courts and governments agencies have created a plethora of topical blacklists of serious offenders. Publication of these lists fulfils both a “naming and shaming” and a deterrence function. Logged minor offences can accumulate and be upgraded to a major offence.

Some entries are automatically deleted after a certain time-period, while serious offences require the offender to undertake a process of “credit repair”. Serious offenders can remain on lists indefinitely and find themselves blocked from activity in certain sectors. The SoCS also establishes red lists to reward compliant behaviour.

Although there are red lists and blacklists specifically for individuals or companies, there is overlap – especially where individuals fulfil a corporate role carrying legal liabilities for areas of a company’s conduct that are under their direct supervision.

If a company is blacklisted for “severe untrustworthiness”, the following entities can receive punishments:

- The company itself;

- The legal representatives of the company;

- The persons directly responsible for the violation.

Joint rewards and punishments to amplify effect of sanctions

The system applies sanctions that go far beyond blacklisting and are in keeping with the principle declared by the Chinese leadership: “Once proven untrustworthy, restrictions should apply everywhere”. Whereas in the past, offenders were sanctioned by one supervising agency or court, they now face a set of punishments jointly imposed by multiple agencies. This greatly amplifies the effect of sanctions, in order to push all societal actors towards law-abiding behaviour.

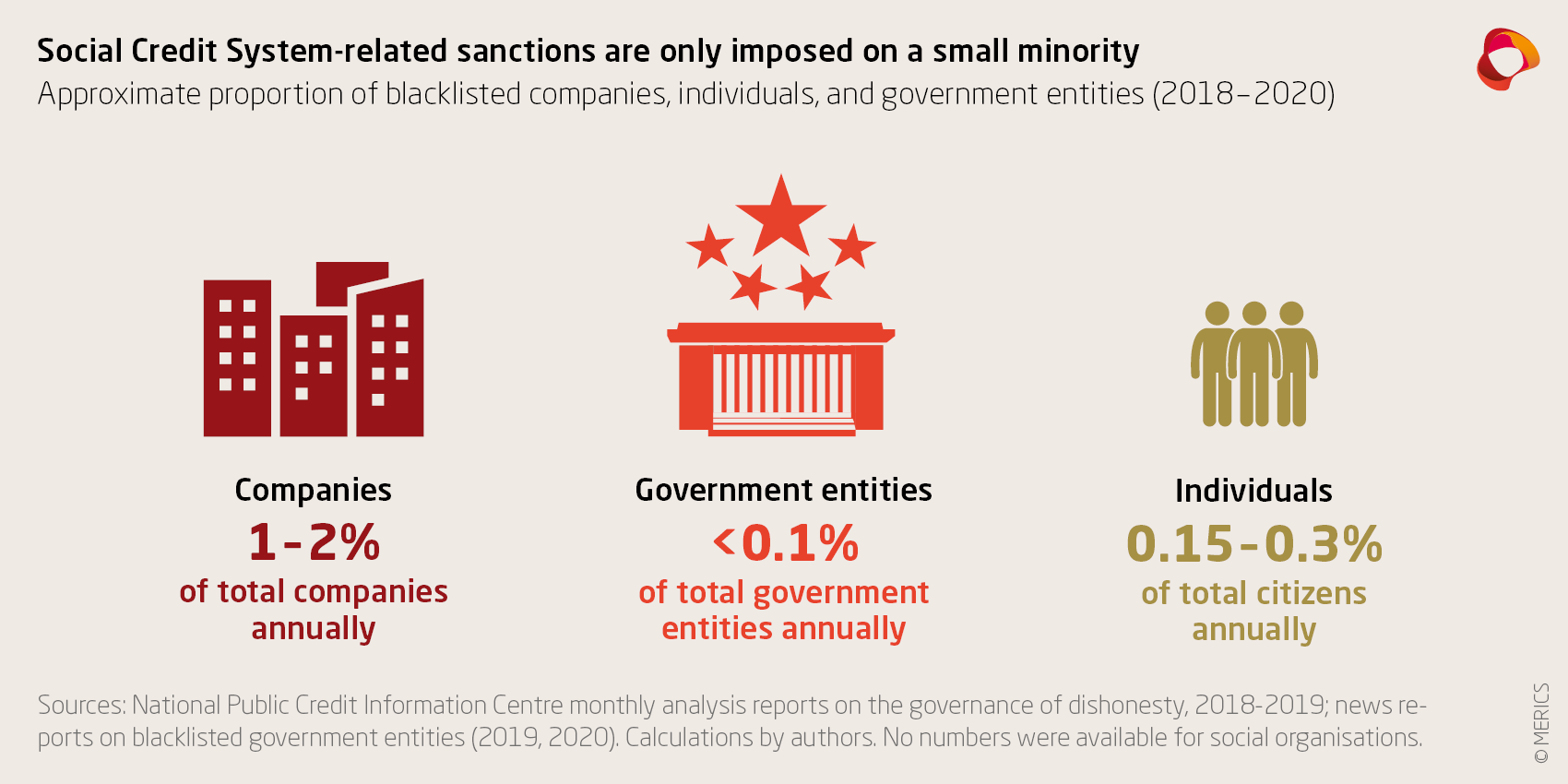

Although the sanctions are severe, our research finds that only a small number of companies and individuals are affected (see exhibit 5). One main purpose of the SoCS is a general deterrence effect through the highly public nature of blacklists and extensive reporting about punishments in state media.

3.3. Campaign-style use for speedy policy implementation

Key rule-making institutions of the SoCS and their local counterparts are permitted to issue formal and normative documents. This makes application highly adaptive. The system is a looseknit body of highly diversified initiatives that has allowed officials to shift their focus – and sanctioning powers – between target groups and sectors in order to prioritise certain laws and regulations. Even at the national level, exhibit 6 shows how the SoCS has targeted different key issues and sectors over time, as evident in the shifting focus on finance or food-safety.

The response to Covid-19 is a case in point: The SoCS was rapidly deployed to track and sanction violations of pandemic prevention measures, to stabilise prices and to later stimulate the safe and orderly return to the workplace. In various cities, citizens that attempted to evade quarantine, refused to have their temperature taken at checkpoints, or intentionally concealed their travel history to hard-hit areas were added to the blacklist.

But in a move that took account of the financial strains wrought by the pandemic, the system was also adjusted to introduce a grace period so debtors (individuals and companies) could avoid being blacklisted and allow flexibility for companies that held back salaries, especially for migrant workers.16

The SoCS’s adaptability is also evident in its changing emphasis within longstanding focus areas, shown here with an analysis of the commerce and industry sectors. As the table in exhibit 7 illustrates, the SoCS keeps expanding to cover new issues on a regular basis; typically, these are linked to new legal stipulations and policy priorities.

As the SoCS framework develops, some issue areas also disappear in new documents. This does not mean these regulations have been abolished, rather that the focus has shifted away from these sub-sectors, or that these sub-sectors have either become sufficiently regulated or obsolete.

Such variety and flexibility make it difficult even for China’s national government to assess the breadth and impact of the SoCS and its subsystems. Nonetheless, the system’s use for targeted policy enforcement has been lauded by the NDRC and is prominent in the planning documents for the next phase, which continue to call for social credit to be used in “issuefocused governance”.17 Against this background, it is to be expected that the SoCS will continue to expand its reach.

3.4. Digitalisation remains limited to "construct" and "share"

Although the system is surrounded by buzzwords like big data and AI, our research has found such implementation remains a lofty goal. Relevant documents of the past years consistently fixate on the basic need to “construct databases and platforms” and “share information”. However, the creation of horizontal and vertical data-sharing highways remains hampered by unclear definitions of different types of credit; by regional and institutional differences in data collected; and the lack of unified standards and centralised storage. Chinese scholars have lambasted the lack of control over many facets of the system.18

This fragmentation brings risks for those affected by the system. Companies need to keep track of various regional and sectoral backlists and check for human error – in one example a foreign company had a serious offence logged on one platform19 but not the other relevant platform. For various sectoral-level blacklist databases, only 10 to 25 per cent of blacklist records are effectively shared with the central Social Credit databases. Even the most well-standardised databases fail to reach over 90 per cent completeness.20

Furthermore, there are increasing indications that the central authorities recognise the dangers of automation for legal and administrative processes and the acceptance of this system. Article 41 of the Administrative Penalties Law revised in January 2021 expresses the intent that digitally collected evidence should require human evaluation.21 As administrative penalties are a significant component of the SoCS, the general message is clear: automation is not the way forward – at least where the SoCS is concerned.

4. Local social credit initiatives show challenges in implementation

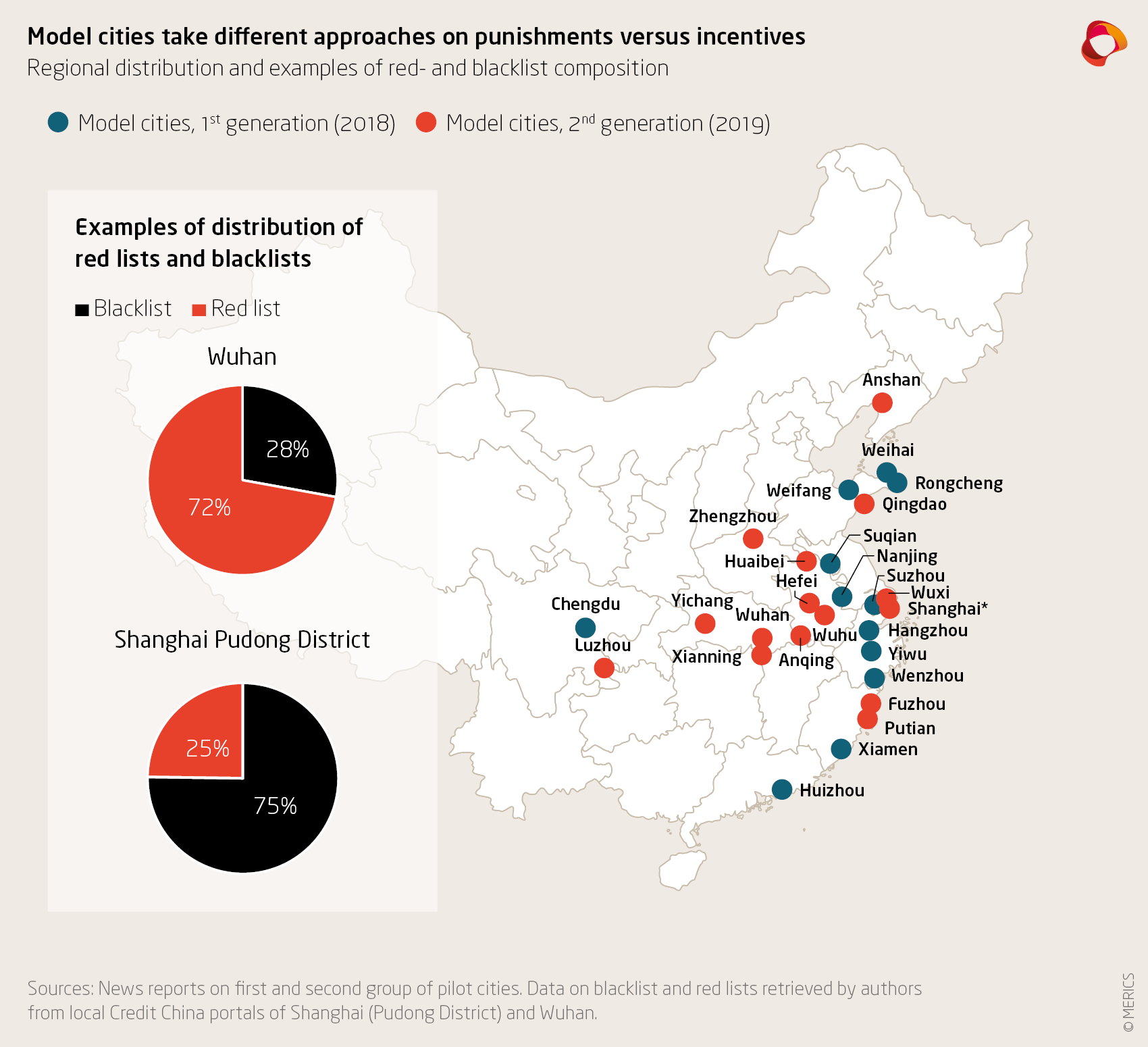

43 pilot cities have launched SoCS projects since 2014, culminating in the selection of 28 model cities between 2018 and 2019 as test beds for nationwide implementation of SoCS. The pilots show that many of the central-level design challenges are reflected in everyday implementation of the system.

4.1. Fragmentation is the name of the game

Although central guidance ensures that the framework remains broadly similar at national and local levels, variations occur as agencies charged with implementing the system at all levels specify this according to local priorities and practices. There are three ways this happens.

First, provinces and cities have used the SoCS framework to address their most pressing policy issues, while other areas are covered less prominently. This is reflected in exhibit 9, where Shanghai and Ningbo, though geographically close, have developed significantly different focus areas in their documents.

Second, while local authorities cannot fully deviate from the national guidance, they can devise plans that add extra dimensions to the system. In December 2020, the State Council reiterated that local authorities have the power to formulate supplementary regulations.22

As they turn abstract central-level documents into actionable and specific plans, this has sometimes entailed broadening the scope through locally specific regulations and targets.

The city of Ningbo’s environmental credit regulations, for example, largely overlap with those in the national regulations. However, it has added provisions for blacklisting entities that are not found in the documents produced by other localities, i.e.,

- Interruption of centralised drinking water sources;

- Receiving criticism in the media at Ningbo-level or above, and then failing to perform correction work;

- Any violations that the environmental protection department “believes” should be included in the blacklist.

The significant leeway for local decision-making is a root cause of uneven or legally ambiguous implementation and can provide vectors for personal influence and abuse of power.

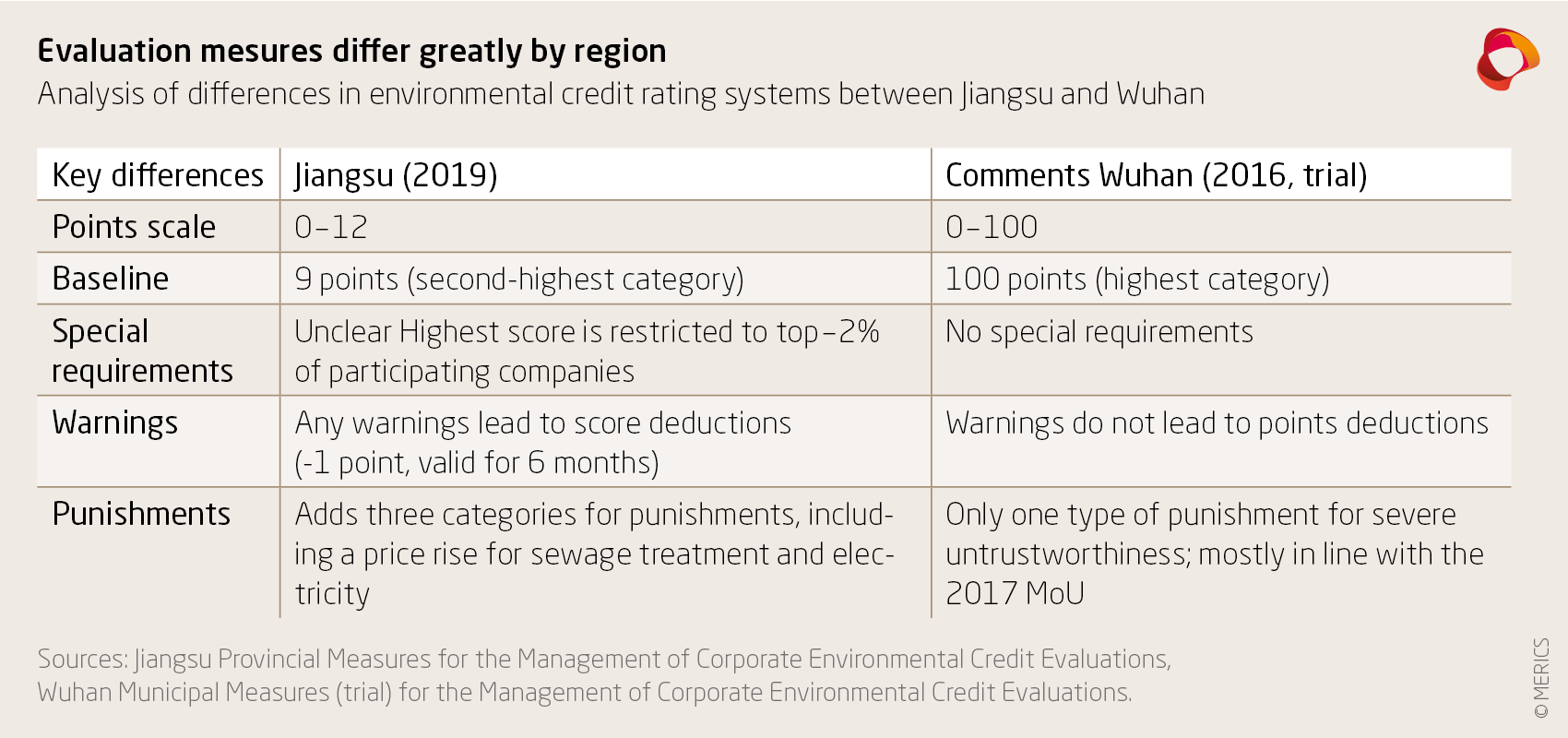

Third, many cities and provinces have implemented proprietary evaluation systems to enforce SoCS measures. These remain much more disjointed than overseas media discussions of China’s Social Credit Systems would suggest and reveal how similar guidelines can be evaluated in widely different ways (see comparison of “environmental ranking” systems in Jiangsu and Wuhan in exhibit 10).24 Companies operating in different cities need to be aware of these differences to navigate any potential impacts on their credit status and local credit files.

4.2. Finding the right amount of punishment

The fragmentation of the SoCS leads to stark differences in reward and punishment applications. What may not lead to a blacklisting in one city may lead to a blacklist in another city.

As at national level, the 28 pilot cities primarily rely on binary red lists and blacklists. Local data sets compiled for this analysis show that just over 700.000 people and companies in these cities have been blacklisted – amounting to merely 0.5 per cent of their combined population.

Many model cities operate well over 20 different blacklists and red lists. The blacklists associated with key areas designated by the central government are relatively well implemented and standardised. For instance, between 70 and 90 per cent of blacklistings target judgement defaulters, i.e., people who refuse to repay loans or court-ordered fines while having the capacity to pay. These are managed by the national court system and are deemed to work effectively already.

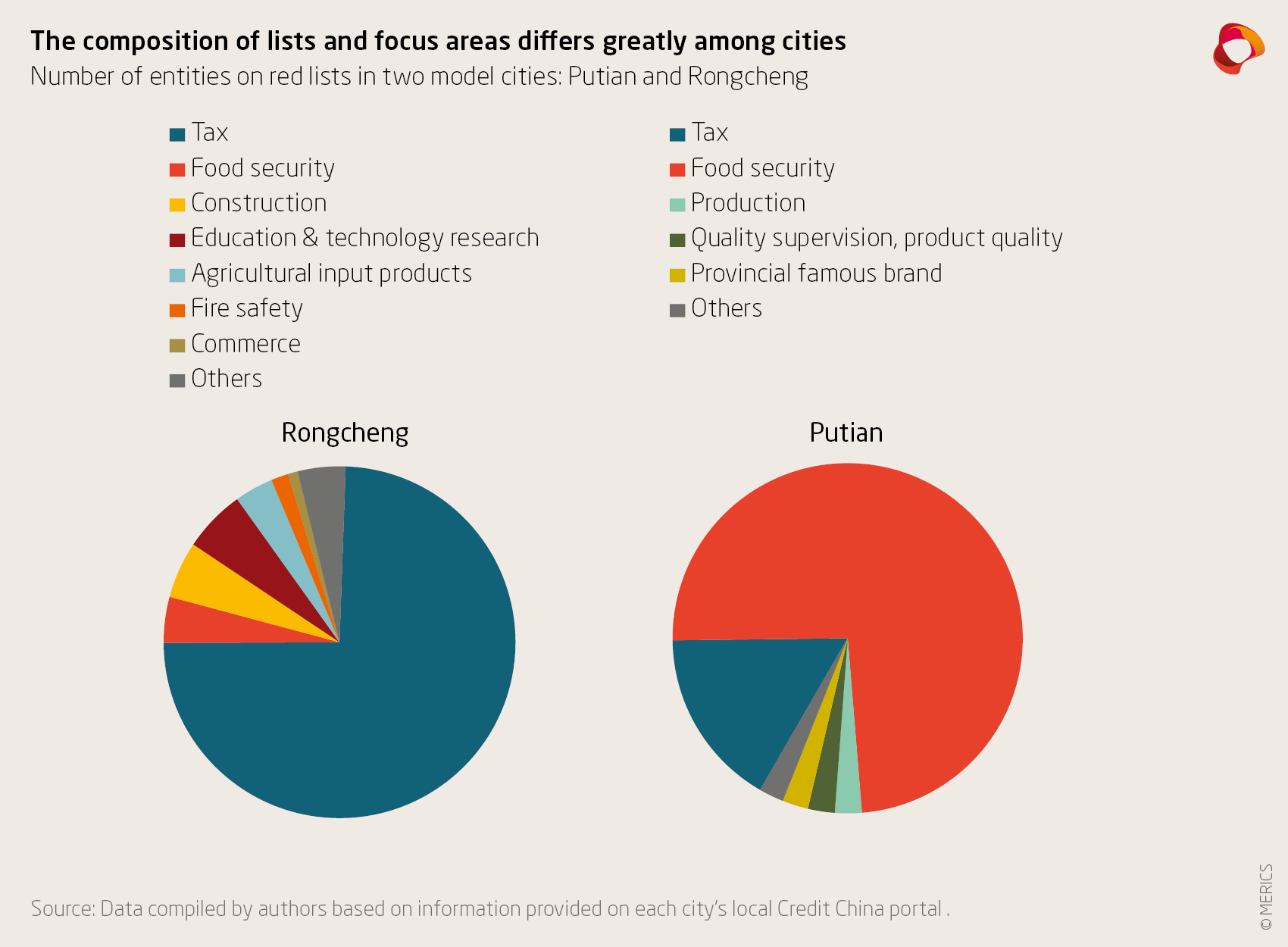

Beyond the few relatively clearly defined issues, categories of offences and encouraged behaviour are murkier. Exhibit 11 shows how cities have devised completely different red lists and apply them differently.

This ambiguity was especially apparent during the Covid-19 epidemic, where model pilot city Zhengzhou indiscriminately red-listed all hospitals assigned to handle Covid-19 patients, i.e., basing special trustworthiness on doing what is required. And other cities blacklisted citizens for as little as not wearing a mask.

In yet another instance, model pilot city Anqing blacklisted a citizen for “causing panic” by posting a video of an ambulance taking away a suspected Covid-19 patient. Chinese media outlets have criticised several of these decisions as arbitrary and irrelevant to the concept of “credit”.26

A further question relates to proportionality. Companies who failed to pay small fines, in one case just 600 CNY, have found themselves on the same blacklist as firms who have defaulted on billion-CNY loans.27 There is therefore an acute risk of “credit” being randomly applied with disproportionate punishments, undermining the party state’s claim that the SoCS would establish fairness and transparency.

4.3. Digital vision meets analogue reality

SoCS implementation in the 28 model cities has highlighted how many of the fundamentals needed for a genuinely high-tech system – e.g., a shared information system, consistent data formatting, etc. – are incomplete. Instead, the SoCS relies heavily on human information collection and low-level digitisation – often little more than the use of Excel worksheets or the WeChat app.

Municipal scoring systems remain rudimentary and resemble incentivised loyalty programmes like those run by airlines. Participation is fully voluntary, and there are no negative incentives beyond losing access to minor rewards. For fear of overreach and pushback, central authorities have banned punishments for low scores and minor offences.28

A tiny percentage of people have taken part over the three years of development. In Xiamen, only 210,059 users activated their account (or roughly 5 per cent); Wuhu has 60,000 (1.5 per cent), and Hangzhou 1,872,316 (15 per cent) – and even fewer regularly use them.29 Scores are also not shared between cities as each one uses different scoring criteria and mechanisms, though some cities have signed conversion agreements.30

Little behavioural data is involved as scoring relies mainly on digitised administrative documents. While early pilots sought to integrate various sources of behavioural and third-party data, this was later discarded. Weihai city officials, for instance, decided to exclude data on jaywalking, running red lights, and parking fees from their scoring system. Similarly, Suzhou’s plan to cooperate with gaming platforms to penalise video gamers through the city’s “Osmanthus” scoring system failed to materialise.

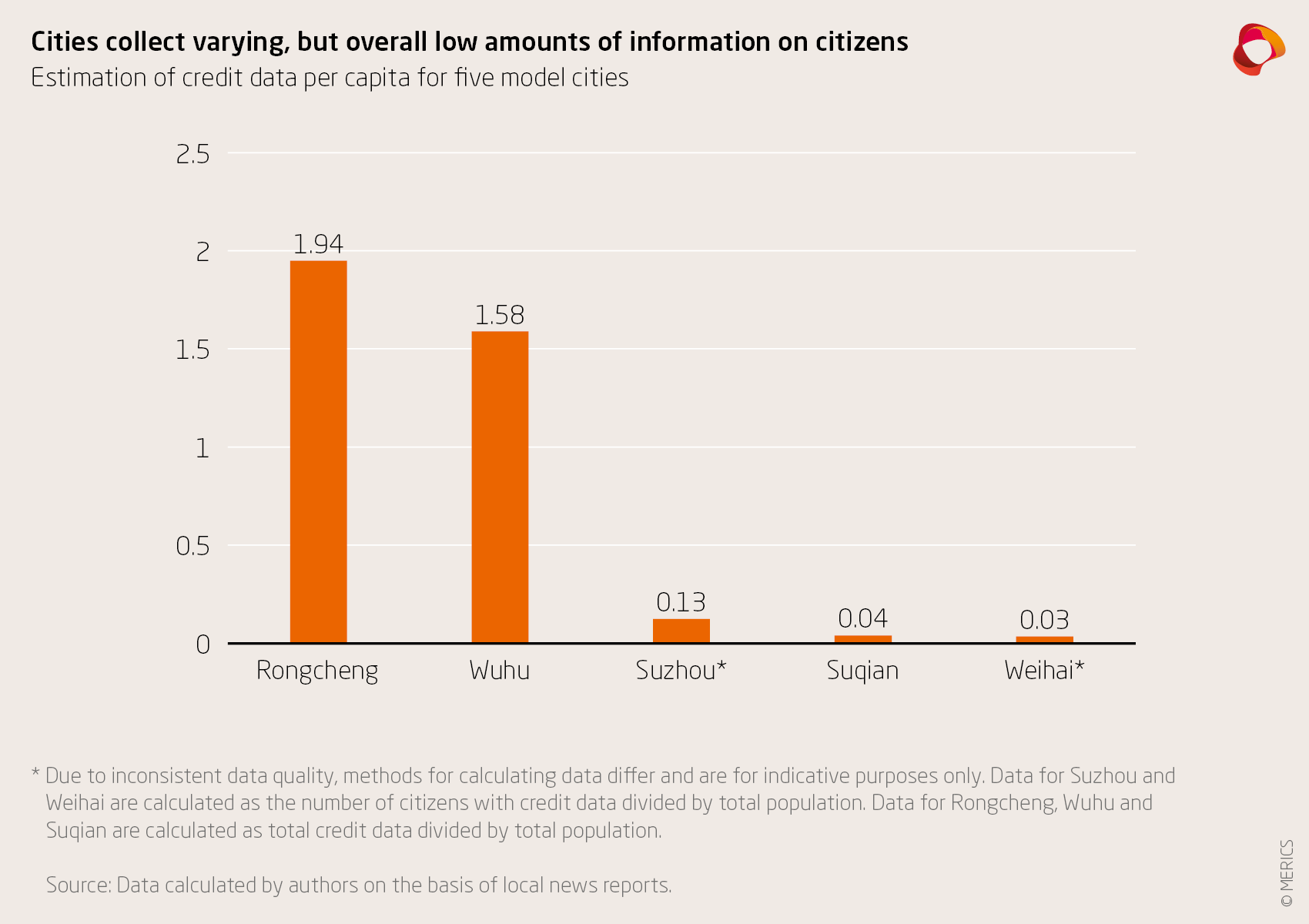

Data-inflation exists on a huge scale. Many model cities have reported collecting over a billion pieces of information (50 billion nationwide), but much of it is low-quality data or irrelevant to social credit, even in its broadest notion. Our investigation shows that even model cities generate at most one to two pieces of actual “credit data” per capita (exhibit 12).32

There are also noticeable differences in data management: some model cities use the official data portal, whereas others periodically upload spreadsheets – sometimes as news items or even images. Hence, information sharing systems remain underdeveloped, meaning one of the central goals set in the Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System has not been met.

Poor data management also affects citizens: 83.9 per cent of respondents to a survey by the China Youth Daily Social Investigation Centre are afraid to be blacklisted without knowing.33

4.4. Standardisation is slowly underway

The State Council is keen to address these challenges: it released several new guidelines between 2019 and 2020 to standardise SoCS implementation practices. In February 2021, the State Administration for Market Regulation published a draft to standardise blacklisting of severely untrustworthy companies.34

In some ways, these appear effective first steps to address aforementioned concerns. The guidelines now more clearly define different levels of untrustworthy conduct, even if they leave room for flexible interpretation. For instance, “severe untrustworthiness” now requires both a serious violation of the law and a major threat to health and safety, disruption of the marketplace, or failure to perform national defence obligations.35 They also standardise blacklisting procedures such as information provision, withdrawal mechanisms, and more.

The new guidance ultimately aims to strictly control implementation of the SoCS and is one of the factors that contributed to halting experiments with over-engineered and highly controversial (often third-party) behavioural data. Possibly as a result, the proportion of blacklisted companies nationwide between 2018 and 2019 dropped 0.21 percentage points to 1.1 per cent.36

Nonetheless, a rapid transition to a fully standardised system is unlikely. As the State Council made clear in December 2020, it wants to retain certain degrees of local flexibility. Combined with the lack of unified standards for data infrastructures and the slow process towards a Social Credit Law, this means that staggered implementation is here to stay.

5. The Social Credit System is a key component of the party state's data-supported rule

The SoCS is part of the jigsaw puzzle of the party state’s vision for governance. It is a vision that relies heavily on data-based approaches and centralised guidance from the CCP, as well as tight surveillance to ensure political and regime stability. The SoCS is not generally tasked with surveillance for political purposes. Rather, there is a clear division of labour between more public and transparent governance initiatives, including the SoCS, and other more covert, repressive ones.

5.1. The CCP's grand vision of data-driven governance

The SoCS is a core component of Beijng’s data-driven governance. It can draw from other digitised monitoring initiatives in order to detect rule breakers. Apart from official court verdicts, its main source of data is various systems and digital governance platforms established as part of the “Internet+Monitoring” or “Internet+Governance” policies. This information ecosystem is much broader in scope than the SoCS and can be drawn on by various government actors.

Similar to the SoCS, “Internet+Monitoring” is not a unified system. It is the umbrella term for the use of multiple channels and mechanisms to collect data and streamline supervision. Examples include real-time monitoring of toxic emissions and or remote video supervision in the food and catering industry. Mobile apps make it easy to enter and collate supervision data.

The underpinning vision is that different government organs join hands to collect vast amounts of data within a coherent information ecosystem, across institutions, regions and administrative levels, as a basis for effective and responsive governance. The central promise to the Chinese public is that comprehensive monitoring will cut red-tape and improve government services and overall safety.

This is presented as a modern and ultimately superior alternative to “Western democracy” with its “outdated” checks and balances such as separation of powers and free media and focus on individual liberties. Beijing is keen to portray China’s containment of Covid-19 as a direct outcome of the competitive advantage of its whole-of-government, data-driven governance system.38

5.2. The party state's growing surveillance ecosystem

The Social Credit System is often incorrectly conflated with China’s surveillance state. In practise, it is a public, relatively transparent system and increasingly curtailed in its reach. But the Chinese party state has other, much more invasive projects at its command. These projects often operate more covertly and act beyond the confines of laws and regulations, in a relatively clear division of labour. These include Golden Shield, Skynet, Safe Cites and Police Clouds, Project Sharp Eyes, and the Integrated Joint-Operations Platform (IJOP) in Xinjiang.39

Interestingly, their key challenges are strikingly similar to the SoCS: Fragmented implementation and inconsistent standards hinder cross-regional integration. Chinese tech giants are playing an increasingly important role here, however. Close cooperation between state authorities and tech firms have driven innovation and growth. The result has been significant progress in online monitoring and almost nationwide camera surveillance coverage, as well as testing out AI and big data analysis, especially in the urban public security sector. In the fight against the pandemic, the government has proudly displayed the benefits of Safe City’s comprehensive camera monitoring.40

The rapid rollout of contact tracing and the Covid-19 QR-based health codes was initially marred by “data islands” as regions set their own standards. But it was also marked by a steep learning curve on how the public and private sector can work together to integrate standards quickly and seamlessly, providing lessons for integration in other areas. The pandemic also revealed the close cooperation and information sharing between government and private companies in the public security sphere.

5.3. Companies will pay a key role in data integration

Early negotiations envisioned participation from China’s tech giants and platforms, which hold a wealth of information on individual behaviour. Although they were eventually excluded from SoCS for fear of unanticipated side-effects and a potential backlash, several payment and consumer platforms have created their own trust-rating initiatives. In fact, Alibaba’s Sesame Credit has become so ubiquitous that is often conflated with the Social Credit System and has strongly contributed to the notion that a unified scoring system exists.

The government still supports the tech sector’s collection of information and use of innovative scoring systems. Above all, there are subtle political gains in the tech sector’s use of highly aligned language on “trust” or “credit.” The messaging to consumers who receive preferential treatment for being trustworthy has a strong habituation and training effect, contributing to the overall vision of a “trust-based” society, in which everybody willingly follows the government’s rules.

At the same time, China’s tech giants remain keen on getting in on the action. They hope to profit from the new drive to integrate data and make it accessible for automated big data and AI-aided interpretation across all the areas outlined above: from SoCS and digital governance to state surveillance. Even a cursory look at calls for bids and advertisements by China’s main tech firms show that they are eager to promote their capabilities in cross-system data and platform integration. A variety of major Chinese companies have already won bids for the construction of SoCS data platforms.42

6. The road ahead for social credit

As the rollout of the Social Credit System moves from phase one to phase two in 2021, the Chinese authorities will continue to build up, streamline, and integrate the system. It has become a cornerstone of Xi’s quest for a more modern and efficient rule and its development will remain a high priority for the years to come.

As once again highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the system is highly flexible and can be rapidly deployed in new fields. Given this record, we should expect the system to continue to be rapidly redeployed as new socio-economic policy priorities come up.

Despite this, current implementation is behind schedule and highly uneven. The system’s highly flexible nature inherently leads to high levels of fragmentation and poor data sharing capabilities. Over the next few years, the Chinese authorities will continue to balance the tightrope of further integration and limitation without stifling flexibility.

The SoCS entails various implications and risks for companies, organisations and individuals. Its decentralised nature makes it exceedingly hard to keep track of. Even though a unified Social Credit Law is on the agenda, it will take years to improve legal certainty and transparency. Despite an increasing focus on credit repair, legal safeguards against wrongful sanctioning through SoCS mechanisms remain underdeveloped. Chinese legal professionals have also called for the need to prevent abuse and reduce joint disciplinary action against citizens.43

Ultimately, a truly automated, big-data and AI driven SoCS is far from reflected in implementation. China’s main focus remains on enabling data integration and sharing between departments and on improving data quality. As the Chinese authorities appear acutely aware of the dangers of automated decision making in this context, this will continue to be a manual process. Hence, it remains important to differentiate the SoCS from initiatives related to e.g. political security, which do show a huge appetite for such solutions.

Since crucial decisions are still taken “offline”, policy makers and potentially affected target groups need to keep analysing vectors for political influence on the SoCS and to regularly engage with companies to analyse blacklisting and sanctions. On the technical side, the collection of increasing amounts of data in the context of the SoCS means higher risks of data leaks and abuse of information.

One key purpose of the SoCS is to drive home the message that non-compliance is not accepted anymore. But the SoCS also serves to enforce repressive and exclusionary norms. Party control has been increasingly legally codified, such as control of political expression online, restrictions on civil society or potential retaliatory measures directed against foreign companies. It is important to systematically analyse the legal and regulatory development in China in the years to come.

Foreign actors need to accept the reality of an expanding Social Credit System in China – and develop strategies to deal with this reality. Most importantly, the SoCS is only a small fraction of China’s monitoring and surveillance capacities. Public security driven surveillance initiatives, in particular, carry much broader rights implications.

The authors would like to thank freelance data scientist Jianyin Roachell for his contribution in building the MERICS Social Credit database as well as Paula Kuls for her support on categorizing normative documents during her internship at MERICS

-

Endnotes

-

1 Sohu (2020a). “年社会信用体系建设十大重点研究方向 (Ten key directions to explore in the construction of the Social Credit System in 2020).” March, 6. https://www.sohu.com/a/378101732_777813. Accessed: Novem-ber 1, 2020.

2 Yu, Qian 余茜 (2020). ““十四五”治理有“数”开新篇 (In the "Fourteenth Five-Year Plan", governance will draw on “data” to open a new chapter).” October 28. http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2020/1028/c40531-31908612.html. Accessed: October 30, 2020.

3 For a detailed analysis of this development see: Knight, Adam (2020). “Technologies of Risk and Discipline in China's Social Credit System.” In: Rogier J. E. H. Creemers and Sue Trevaskes (eds). Law and the Party in Xi Jinping's China: Ideology and Organization, 273-254; Trivium (2019). “Understanding China’s Social Credit Sys-tem.” Trivium Primer. http://socialcredit.triviumchina.com/what-is-social-credit/. Accessed: October 10, 2020.

4 Sohu (2020b): “习近平:要把法治工作重点放在完善制度环境上,加强社会信用体系建设 (Xi Jinping: In build-ing rule by law, we must focus on improving the systemic environment and strengthen the construction of the Social Credit System)”. February 27. https://www.sohu.com/a/298187739_100013182. Accessed: October 12, 2020.

5 Xinhua (2020). “近平在中央全面依法治国工作会议上强调 坚定不移走中国特色社会主义法治道路 为全面建设社会主义现代化国家提供有力法治保障 (Xi Jinping emphasizes need to unswervingly follow the path of Socialist Rule of Law with Chinese Characteristics at Central Committee's Work Conference on Comprehensive Rule of Law, in order to provide a strong legal foundation for the construction of a modern socialist country)”. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2020-11/17/c_1126751678.htm. Accessed: November 25, 2020.

6 CCP Central Committee (2020).

7 Knight (2020); Zhang, Chenchen (2020). “Governing (through) Trustworthiness: Technologies of Power and Subjectification in China’s Social Credit System”. Critical Asian Studies, 2020, 1–24.

8 The analysis presented here and in the following sections is based on the MERICS Social Credit System data-base. This consists of 1456 documents published by national and provincial authorities between 2003 and 2020, retrieved from the Credit China and State Council document repositories. Separate to this, the database also includes around 1000 documents published by a selection of Chinese cities.

9 Laws and regulations can refer to SoCS for implementation and enforcement to varying degrees, from requir-ing information to be entered into SoCS mechanisms or explicitly outlining blacklistable offenses. See e.g.: For-eign Investment Law of the PRC (2019), arts. 34, 38; Vaccine Administration Law of the PRC (2019), arts. 23, 72; Biosecurity Law of the PRC (2020), art. 26.

10 A key recent document can be found in English at: China Law Translate, trans. (2020). "Guiding Opinions on Further Regulating the Scope of Inclusions in Public Credit Information, Punishments for Untrustworthiness, and Credit Restoration to Build Long-Term and Effective Mechanisms for Establishing Creditworthiness (Draft for Solicitation of Public Comments)". https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/futher-regulating-social-credit/. Accessed November 2, 2020.

11 The Paper (2020). “国家发改委:社会信用法草案正征求各地方和相关部门意见 (National Development and Reform Commission: the draft for the Social Credit Law is currently seeking opinions from local and relevant departments)”. December 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_10401166. Accessed: February 4, 2021.

12 Research by authors on Credit China portal and debt-defaulter blacklist. Knight

13 (2020); Trivium (2019).

14 Su, Alice (2020). “Threats of arrest, job loss and surveillance. China targets its ‘model minority’”. September 23. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-09-23/inner-mongolia-china-model-minority-crackdown. Accessed: October 22, 2020.

15 Boxun (2018). “家长成老赖孩子不能上学?这所中学的招生政策火了 (Children of “debtors” cannot go to school? The enrollment policy of this middle school is drawing fiery debate)”. May, 1. https://www.boxun.com/news/gb/misc/2018/05/201805010728.shtml. Accessed: November 2, 2020.

16 Brussee, Vincent (2020). "No Credit for Culprits". Mercator Institute for China Studies. July 21. https://merics.org/en/analysis/no-credit-culprits. Accessed: October 10, 2020.

17 NDRC (2019). “国家发改委:社会信用体系建设重点领域专项治理成效显著 (NDRC: The Social Credit System construction has achieved remarkable results in issue-focused governance of key areas).” https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/ztzl/cyzl/2019cy/cxcy/201901/t20190123_1188559.html. Accessed: October 28, 2020.

18 Lin, Junyue (2020). “On the Identification of the Nature of Social Credit System and Its Practical Significance.” Credit Reference 征信 9: 1–7; Jiang, Kaiyuan (2020). “Development and Application of the Public Credit Infor-mation Exchange Standard.” Standard Science 7: 57–61; Tang, Gui, and Haojie Chen (2020). “Innovative Research on the Construction of New Industry Credit System with Chinese Characteristics.” Exploration of Economic Issues 2020/8: 44–49.

19 Case samples collected from Credit China by authors.

20 Trivium China (2020). “China’s Corporate Social Credit System: Context, Competition, Technology and Geopol-itics.” https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Chinas_Corporate_Social_Credit_System.pdf. Accessed: January 7, 2021.21 Xinhua (2021). ”中华人民共和国行政处罚法 (Administrative Penalties Law of the People's Republic of China)”. January 23. http://m.xinhuanet.com/2021-01/23/c_1127015256.htm. Accessed: January 27, 2021.

22 State Council (2020). "国务院办公厅关于进一步完善失信约束制度构建诚信建设长效机制的指导意见 (State Council Office Guiding Opinions regarding the Further Improving the Dishonesty Constraint System and Estab-lishing a Long Term Mechanism for Integrity Construction).“ http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-12/18/content_5570954.htm. Accessed: January 7, 2021.

23 Ningbo Credit (2016).” 宁波市环境违法“黑名单”管理办法(试行) (Ningbo Municipal Trial Measures for the Management of the Blacklist for Illegal Environmental Actions)”. https://www.nbcredit.gov.cn/art/2016/12/23/art_14_4989.html. Accessed: December 15, 2020.

24 Department of Ecology and Environment of Jiangsu Province (2020). “江苏省企事业环保信用评价办法政策解读 (Policy Interpretation for the Jiangsu Provincial Management of the Corporate Environmental Credit Evalua-tions)”. http://hbt.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2020/5/27/art_74111_9186767.html. Accessed: December 15, 2020; Credit Wuhan (2015). “武汉市企业环境信用评价办法(试行)(Wuhan Trial Measures for the Management of the Corporate Environmental Credit Evaluations)”. https://credit.wuhan.gov.cn/front/article/29428.html. Accessed: December 15, 2020.

25 Brussee, Vincent (2020).

26 Xinhua Credit (2020). "公共场所不戴口罩算失信?社会信用制度要防滥用 (Not Wearing a Mask in Public Places Counts as Trustbreaking? Social Credit System Should Prevent Abuse)." May 20. http://www.jinshui.gov.cn/xydt/3321286.jhtml. Accessed: November 3, 2020.

27 Tencent / Wuhan Court (2019). "武汉公布第5批失信被执行人名单:有人因欠593.55元被限制出境 (Wu-han Publishes Fifth Batch of Trust-Breakers: People Have Been Banned from Going Abroad for Owing 593.55 CNY)." October 31. https://page.om.qq.com/page/OxNwtSojeWIoadlUTuEStOsg0. Accessed: October 30, 2020.

28 Zhang C. (2020).

29 Zhang, Chenchen (2020); Sohu (2018). “’信用让生活更便利’—— 芜湖新闻频道对乐惠分应用场景进行采访报道 (‘Credit Makes Life More Convenient‘ - Wuhu News Channel Interviews and Reports on the Application Sce-nario’s of Lehui Points).” September 3. https://www.sohu.com/a/251674535_818105. Accessed: November 2, 2020; Sohu (2020). “速领!杭州试点’信用码’,持’蓝码、绿码’去景区、酒店、停车可享优惠! (Hangzhou Trials ‘Credit Code’, Holders of Blue and Green Codes Can Enjoy Discounts at Scenic Sites, Hotels, and Parking).” April 30. https://www.sohu.com/a/392234158_160905. Accessed: November 2, 2020.

30 The only two publicly-known instances are Hangzhou-Xiamen and Hangzhou-Quzhou: Hangzhou Daily (2020). “浙江杭州、福建厦门:杭州“钱江分”与厦门“白鹭分”互认 (Hangzhou and Xiamen: Hangzhou’s Qianjiang Points and Xiamen’s Egret Points Have Become Mutually Interoperable).” April 30. http://www.bcpcn.com/articleShow?d=95456. Accessed: November 3, 2020; Sohu (2020). “速领!杭州试点“信用码”,持“蓝码、绿码”去景区、酒店、停车可享优惠! (Hangzhou Trials “Credit Code”, Holders of Blue and Green Codes Can Enjoy Discounts at Scenic Sites, Hotels, and Parking).” April 30. https://www.sohu.com/a/392234158_160905. Accessed: November 2, 2020.

31 Sohu (2020c). "威海医保信用信息共享至社会信用管理中心,纳入'海贝分'管理 (Weihai Medical Insurance Credit Information Is Shared to the Social Credit Management Center and Included in the Haibei Points Man-agement)." August 28. https://k.sina.cn/article_5328858693_13d9fee4502000y11k.html?from=news&subch=onews. Accessed: November 3, 2020.

32 Legal Daily (2018). “苏州打造市民信用评价’桂花分’ (Suzhou Builds Citizen Credit Rating ‘Osmanthus Points’).” August 16. http://www.legaldaily.com.cn/zt/content/2018-08/16/content_7619942.htm. Accessed: November 3, 2020; Xinhua News (2017). "(市长谈信用)芜湖:五大体系推进诚信建设制度化 (Mayor Talks About Credit - Wuhu: Five Big Systems Promote Institutionalisation of Integrity Construction)." October 14. http://xinhua-rss.zhongguowangshi.com/13701/5309965205194152973/2404929.html. Accessed: November 3, 2020; CreditHB (2018). "西楚分:让守信主体拥有更多获得感 (Xichu Points: Let Trustworthy Entities Have More Sense of Achievement)." May 23. http://www.credithb.org/content/?1745.html. Accessed: 3 November 2020; Xinhua (2018). "山东荣成:让信用成为城市'金字招牌' (Shandong Rongcheng: Let Credit Become a City’s “Gold Signboard')." September 27. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2018-09/27/c_1123488320.htm. Accessed: November 3, 2020; Weihai News (2019). "在威海,'海贝分'高者可享22项惠民政策 (In Weihai, Those with High 'Haibao Points' Can Enjoy 22 Beneficial Policies)." January 22. https://www.whnews.cn/news/node/2019-01/22/content_7054576.htm. Accessed: November 3, 2020.

33 Hao, Jing (2020). "论行政法视域下正当程序对信用监管机制的规制 (On the Regulation of the Credit Supervi-sion Mechanism from the Perspective of Administrative Law)." Journal of Hebei Youth Administrative Cadres College 32(5): 82–87.

34 China Law Translate, trans. (2021). Measures for Managing the List of Untrustworthy Enterprises with Seri-ous Violations (Draft Revisions for Solicitation of Public Comments). https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/bad-business/. Accessed: February 15, 2021.

35 China Law Translate, trans. (2020). "Guiding Opinions on Further Regulating the Scope of Inclusions in Public Credit Information, Punishments for Untrustworthiness, and Credit Restoration to Build Long-Term and Effec-tive Mechanisms for Establishing Creditworthiness (Draft for Solicitation of Public Comments)." https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/futher-regulating-social-credit/. Accessed: November 2, 2020.

36 National Information Centre (2020). "城市信用状况监测 推动社会信用体系建设显实效 (Urban Credit Status Monitor, Effective Results of the Promotion the Construction of the Social Credit System)." China Credit 中国信用 2020(2): 67–72.

37 State Council (2019). “国务院办公厅关于加快推进社会信用体系建设 构建以信用为基础的新型监管机制的指导意见 (Guiding Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Accelerating the Construction of the Social Credit System and Building a New Monitoring Mechanism with Social Credit as its Foundation).” http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-07/16/content_5410120.htm. Accessed: October 15, 2020.

38 State Council Information Office (2020). “White Paper: Fighting COVID-19: China in Action.” http://english.www.gov.cn/atts/stream/files/5edc549dc6d0cc300eea778c. Accessed: October 25, 2020.

39 For a detailed discussion of these different initiatives, see: Peterson, Dahlia (2020). “Designing Alternatives to China’s Repressive Surveillance State.” CSET Policy Brief (October 2020). https://cset.georgetown.edu/research/designing-alternatives-to-chinas-repressive-surveillance-state/. Accessed: November 6, 2020; ChinaFile (2020). “State of Surveillance: Government Documents Reveal New Evidence on China’s Efforts to Monitor Its People.” October 30. https://www.chinafile.com/state-surveillance-china. Accessed: November 6, 2020; Human Rights Watch (2019). “China’s Algorithms of Repression: Reverse Engineering a Xinjiang Police Mass Surveillance App.” May 1. https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass. Accessed: November 6, 2020.

40 von Carnap et al. (2020).

41 Trivium (2020).

42 Trivium (2020).

43 Xu, Yangyang 徐杨杨 (2020). “社会信用体系建设背景下的信用应用创新研究 (Research on Innovation in Credit Applications against the Background of the Construction of the Social Credit System)”. Attention 关注 2020(2): 14-15; Sohu (2020). “该立一部什么样的社会信用法? (Establish What Kind of a Social Credit Law?)”. July 10. https://www.sohu.com/a/400990633_777813. Accessed November 3, 2020; Xiao, Zhenyu 肖振宇, Houru Weng 翁后茹, and Yang Sun 孙阳 (2020). ‘县域城市信用体系建设的实践与思考 ——以江苏省昆山市为例 (Practice and Reflection on the Construction of County City Credit System — A Case of Kunshan City. Jiangsu Province)’.